7

DETERMINING THE IDENTITY OF THE TEXT

By way of a framework for the following discussion I shall use Burgon's seven "Notes of Truth." They are:

1. Antiquity, or Primitiveness;

2. Consent of Witnesses, or Number;

3. Variety of Evidence, or Catholicity;

4. Respectability of Witnesses, or Weight;

5. Continuity, or Unbroken Tradition;

6. Evidence of the Entire Passage, or Context;

7. Internal Considerations, or Reasonableness.[1]

The "Notes of Truth"

Antiquity, or Primitiveness

A reading, to be a serious candidate for the original, should be old. If there is no attestation for a variant before the middle ages it is unlikely to be genuine. A word of caution is required here, however. Not only may age be demonstrated by a single early witness, but also by the agreement of a number of later independent witnesses—their common source would have to be a good deal older. Sturz has a good discussion of this point.[2] But any reading that has wide late attestation almost always has explicit early attestation as well.

To give a concrete definition to the idea of "antiquity" I will take the year 400 A.D. as an arbitrary cut-off point. Allowing only those witnesses who "spoke" before that date, "antiquity" would include over seventy Fathers, Codices Aleph and B and a number of fragmentary uncials, the early Papyri and the earliest Versions. By way of specific illustration, ever since 1881 the word "vinegar" in Matt. 27:34 has been despised as a "late, Byzantine" reading—but what is the verdict of "antiquity"? Against it are Codices Aleph and B, the Latin and Coptic versions, the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, the Gospel of Nicodemus, and Macarius Magnes—seven witnesses. In favor of it are the Gospel of Peter, Acta Philippi, Barnabas, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Celsus, Origen, pseudo-Tatian, Athanasius, Eusebius of Emesa, Theodore of Heraclea, Didymus, Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory Nazianzus, Ephraem Syrus, Lactantius, Titus of Bostra and the Syriac version—eighteen witnesses.[3] The witnesses for "vinegar" are both older and more numerous than those for "wine."

Of course, age by itself is not enough. We have seen that most significant variants date to the second century. What we are after is the oldest reading, the original, and to judge between competing old readings we need other considerations.

Consent of Witnesses, or Number

A reading, to be a serious candidate for the original, should be attested by a majority of the independent witnesses. Please recall the discussion of weighing and counting given above. A reading attested by only a few witnesses is unlikely to be genuine—the fewer the witnesses the smaller the likelihood. Conversely, the greater the majority the more nearly certain is the originality of the reading so attested. Wherever the text has unanimous attestation the only reasonable conclusion is that it is certainly original.[4]

Even Hort acknowledged the presumption inherent in superior number. "A theoretical presumption indeed remains that a majority of extant documents is more likely to represent a majority of ancestral documents at each stage of transmission than vice versa."[5] The work of those who have done extensive collating of MSS has tended to confirm this presumption. Thus Lake, Blake, and New found only orphan children among the MSS they collated, and declared further that there were almost no siblings—each MS is an "only child."[6] This means they are independent witnesses, in their own generation. In Burgon's words:

. . . hardly any have been copied from any of the rest. On the contrary, they are discovered to differ among themselves in countless unimportant particulars; and every here and there single copies exhibit idiosyncrasies which are altogether startling and extraordinary. There has therefore demonstrably been no collusion—no assimilation to an arbitrary standard,—no wholesale fraud. It is certain that every one of them represents a MS., or a pedigree of MSS., older than itself; and it is but fair to suppose that it exercises such representation with tolerable accuracy.[7]

In accordance with good legal practice, it is unfair to arbitrarily declare that the ancestors were not independent; some sort of evidence must be produced. It has already been shown that Hort's "genealogical evidence," with reference to MSS, is fictitious. But it remains true that community of reading implies a common origin, unless it is the type of mistake that several scribes might have made independently. What is in view here is the common origin of individual readings, not of MSS, but where several MSS share a large number of readings peculiar to themselves their claim to independence is evidently compromised throughout. (The "Claremont Profile Method"[8] gives promise of being an effective instrument for plotting the relationship between MSS.)

However, there is one situation where community of reading does not compromise independence. If the common origin of a reading is the original, then the MSS that have it may not be disqualified; their claim to independence remains unsullied. Of course, we do not know, at this stage in the inquiry, which is the original reading, but some negative help is immediately available. If one or more of the competing variants is an obvious mistake, then those MSS which attest such variants are disqualified, at that one point (recall that genealogy was supposed to be based upon community in error).

For the rest, the history of transmission becomes an important factor, but to trace it with confidence we must take account of at least two further considerations. In the meantime, the independent status of MSS agreeing in readings that could be original must be held in abeyance—there is not sufficient evidence to disqualify them, yet.

Variety of Evidence, or Catholicity

A reading, to be a serious candidate for the original, should be attested by a wide variety of witnesses. By variety is meant, in the first place, many geographical areas, but also different kinds of witnesses—MSS, Fathers, Versions, and Lectionaries. The importance of "variety" is well stated by Burgon.

Variety distinguishing witnesses massed together must needs constitute a most powerful argument for believing such Evidence to be true. Witnesses of different kinds; from different countries; speaking different tongues:—witnesses who can never have met, and between whom it is incredible that there should exist collusion of any kind:—such witnesses deserve to be listened to most respectfully. Indeed, when witnesses of so varied a sort agree in large numbers, they must needs be accounted worthy of even implicit confidence. . . . Variety it is which imparts virtue to mere Number, prevents the witness-box from being filled with packed deponents, ensures genuine testimony. False witness is thus detected and condemned, because it agrees not with the rest. Variety is the consent of independent witnesses, . . .

It is precisely this consideration which constrains us to pay supreme attention to the combined testimony of the Uncials and of the whole body of the Cursive Copies. They are (a) dotted over at least 1000 years: (b) they evidently belong to so many divers countries, —Greece, Constantinople, Asia Minor, Palestine, Syria, Alexandria, and other parts of Africa, not to say Sicily, Southern Italy, Gaul, England, and Ireland: (c) they exhibit so many strange characteristics and peculiar sympathies: (d) they so clearly represent countless families of MSS., being in no single instance absolutely identical in their text, and certainly not being copies of any other Codex in existence,—that their unanimous decision I hold to be an absolutely irrefragable evidence of the Truth.[9]

Variety helps us evaluate the independence of witnesses. If the witnesses which share a common reading come from only one area, say Egypt, then their independence must be doubted. It seems quite unreasonable to suppose that an original reading should survive in only one limited locale. If the history of the transmission of the text was largely normal, as I believe it was, then we must conclude that a reading found only in one limited area cannot be original. It follows that witnesses supporting such readings are disqualified, just like those supporting obvious mistakes—they are not independent, at that point. They are disqualified as independent witnesses, but their combined testimony still counts as one vote; their common ancestor is still an independent witness.

As Burgon points out, it is variety that lends validity to number, because variety implies independence. Conversely, lack of variety implies dependence, which is why a reading that lacks variety of attestation has little claim upon our confidence. It is an eloquent testimony to the soporific effects of the W-H theory (with its "genealogy") that subsequent scholarship has largely ignored the factor of variety in attestation. There has been an occasional murmur of disquiet,[10] but nothing approaching a recognition of the true place that "variety" should have in the practice of New Testament textual criticism. Burgon stated the obvious when he said:

Speaking generally, the consentient testimony of two, four, six, or more witnesses, coming to us from widely sundered regions is weightier by far than the same number of witnesses proceeding from one and the same locality, between whom there probably exists some sort of sympathy, and possibly some degree of collusion.[11]

Closely allied to variety is the factor of continuity.

Continuity, or Unbroken Tradition

A reading, to be a serious candidate for the original, should be attested throughout the ages of transmission, from beginning to end. If the history of the transmission of the text was at all normal, we would expect the original wording "to leave traces of its existence and of its use all down the ages."[12] If a reading or tradition died out in the fourth or fifth century we have the verdict of history against it. If a reading has no attestation before the twelfth century, it is certainly a late invention.[13]

Where there is variety there is almost always continuity as well, but they are not identical considerations. Continuity also helps us in evaluating the independence of witnesses. Readings which form little eddies in the late "Byzantine" stream convict their supporters of dependence at those points. Readings which enjoy both a wide variety and continuity of attestation vindicate the independence of their supporters. Apart from some objective demonstration to the contrary (such as Hort claimed for "genealogy") it is not fair to reject the independence of such witnesses. They must be allowed to vote. The punch line is this: The majority of the extant MSS emerge as independent witnesses, in their generation, and they must be counted until such a time as complete collations permit an empiric grouping, like F. Wisse did in Luke 1, 10 and 20.[14]

Hort, followed by Zuntz and others,[15] rejected this consideration absolutely. But the reader is now in some position to judge for himself. Since there was no authoritative revision of the text in 300 A.D., or any other time, and since the evidence indicates a reasonably normal history of transmission, how can the validity of "continuity" as a "note of truth" be reasonably denied? In my view, the factors of number, variety, and continuity form the backbone of a sound methodology in textual criticism. They form a three-strand rope, not easily broken. But there are several other considerations which are helpful, on occasion and in their way.

Respectability of Witnesses, or Weight

Whereas the previous four "notes" have centered on readings, this one centers on the witnesses. Whereas the "notes" of number, variety, and continuity help us to evaluate the independence of witnesses, this one is concerned with the credibility of a witness judged by its own performance. "As to the Weight which belongs to separate Copies, that must be determined mainly by watching their evidence. If they go wrong continually, their character must be low. They are governed in this respect by the rules which hold good in life."[16]

The evidence offered above in the discussion of the oldest MSS and of weighing versus counting must suffice to illustrate both the importance and the applicability of this "note." The oldest MSS can be objectively, statistically shown to be habitually wrong, witnesses of very low character, therefore. Their respectability quotient hovers near zero. Their great age only renders their behavior the more reprehensible. (I am reminded of young King Henry's rebuke to Falstaff.)[17] In particular, I fail to see how anyone can read Hoskier's Codex B and its Allies with attention and still retain respect for B and Aleph as witnesses to the New Testament text—they have been weighed and found wanting.

Since the modern critical and eclectic texts are based precisely on B and Aleph and the other early MSS, blind guides all, it is clear that modern scholars have severely ignored the consideration of respectability, as an objective criterion. I submit that this "note of truth" must be taken seriously; the result will be the complete overthrow of the type of text currently in vogue.

Evidence of the Entire Passage, or Context

The "context" spoken of here is not what is usually understood by the word but is concerned with the behavior of a given witness in the immediate vicinity of the problem being considered. It is a specific and limited application of the previous "note."

As regards the precise form of language employed, it will be found also a salutary safeguard against error in every instance, to inspect with severe critical exactness the entire context of the passage in dispute. If in certain Codexes that context shall prove to be confessedly in a very corrupt state, then it becomes even self-evident that those Codexes can only be admitted as witnesses with considerable suspicion and reserve.[18]

An excellent illustration of the need for this criterion is furnished by Codex D in the last three chapters of Luke—the scene of Hort's famous "Western non-interpolations." After discussing sixteen cases of omission (where W-H deleted material from the TR) in these chapters, Burgon continues:

The sole authority for just half of the places above enumerated [Luke 22:19-20; 24:3, 6, 9, 12, 36, 40, 52] is a single Greek codex,—and that, the most depraved of all,—viz. Beza's D. It should further be stated that the only allies discoverable for D are a few copies of the old Latin. . . . When we reach down codex D from the shelf, we are reminded that, within the space of the three chapters of S. Luke's Gospel now under consideration, there are in all no less than 354 words omitted: of which, 250 are omitted by D alone. May we have it explained to us why, of those 354 words, only 25 are singled out by Drs. Westcott and Hort for permanent excision from the sacred Text? Within the same compass, no less than 173 words have been added by D to the commonly Received Text,—146, substituted,—243 transposed. May we ask how it comes to pass that of those 562 words not one has been promoted to their margin by the Revisionists?[19]

The focus here is upon Westcott and Hort. According to their own judgment, codex D has omitted 329 words from the genuine text of the last three chapters of Luke plus adding 173, substituting 146 and transposing 243. By their own admission the text of D here is in a fantastically chaotic state, yet in eight places they omitted material from the text on the sole authority of D! With the scribe on a wild omitting spree, to say nothing of his other iniquities, how can any value be given to the testimony of D in these chapters, much less prefer it above the united voice of every other witness?!?!

This Note of Truth has for its foundation the well-known law that mistakes have a tendency to repeat themselves in the same or in other shapes. The carelessness, or the vitiated atmosphere, that leads a copyist to misrepresent one word is sure to lead him into error about another. The ill-ordered assiduity which prompted one bad correction most probably did not rest there. And the errors committed by a witness just before or just after the testimony which is being sifted was given cannot but be held to be closely germane to the inquiry.[20]

Apart from the patent reasonableness of Burgon's assertion, the studies of Colwell in P45, P66, and P75 have demonstrated it to be true. We have already seen how Colwell was able, on the basis of the pattern of their mistakes, to give a clear and different characterization to each of the three copyists.[21] Here again, this "note of truth" seems to be completely ignored by current scholars. Why? Is its validity not obvious?

Internal Considerations, or Reasonableness

This "note" has nothing to do with the "internal evidence" of which we have heard so much. It is only rarely applicable and concerns readings which are grammatically, logically, geographically, or scientifically impossible. Burgon considered that pantwn, the reading of B,D in Luke 19:37 is a grammatical impossibility; that kardiaiV, the reading of À,A,B,C,D, etc. in 2 Cor. 3:3 is a logical impossibility; that ekaton exhkonta, the reading of À,K,N,Q,P in Luke 24:13 is a geographical impossibility; that eklipontoV, the reading of P75,À(B)C,L in Luke 23:45 is a scientific impossibility (the Passover always coincides with a full moon, and a full moon cannot eclipse the sun); and that autou, the reading of À,B,D,L in Mark 6:22 is an historical impossibility (it contradicts both Matthew and Josephus).[22]

I would offer oV, the reading of Aleph and three cursives in 1 Tim. 3:16 as a fine example of a grammatical impossibility—it is a nominative relative pronoun with no antecedent in the context; I regard the claim that it came from a primitive hymn to be gratuitous, a desperate effort to save an obviously bad reading. In the following section there will be some further examples.

Although Burgon apparently limited the use of this "note" to readings that he considered to be virtually impossible, I will expand it in the direction of what is normally understood by "reasonableness", namely the requirements of the context, which I consider to be an important consideration. A variant that is at odds with the context is suspect.

Examples and Implications

The first edition of this book was criticized because it contained no examples to show how these principles apply to specific cases. The first revision included appendices D and E, which alleviated the criticism somewhat. In the intervening years my thinking on this subject has matured considerably, in part because of significant research that has become available in that interim, so I now propose to discuss some specific examples—they each offer some difficulty that has theoretical implications, and these will be discussed. One fundamental question for Majority Text theory is this: "Is there a ceiling above which a reading may be considered 'safe' or secure; that is, beyond reasonable challenge?" Personally, I have tended to regard 80% as such a ceiling; I believe others would settle for 70%. But what do we do if the attestation falls below 70% of the MSS, or below 60%, or below 50%? I believe we must agree with Burgon that "majority" cannot be the only criterion.

1) Example—Luke 3:33

According to the International Greek New Testament Project for Luke, some 60% of the Greek MSS insert tou Iwram between "Aram" and "Hesron".[23] But, out of 27 extant uncials only nine include "Joram"; 18 do not and they are supported by the three earliest Versions. ("Joram" was possibly an early corruption of Aram [as per the ancestor of MS 1542] that was subsequently conflated with it; the conflation survives in a large segment of the "Byzantine" tradition, which is seriously divided here.)

1) Implications

"Joram" has a clear majority attestation, albeit a weak one. However, the earliest MS to include it is from the 8th century; all earlier MSS lack it. In terms of Burgon's "Notes of Truth," Joram wins in "Number" but loses in "Antiquity," "Variety" and "Continuity". I believe Burgon would agree that "Joram" should be regarded as an interpolation.

2) Example—Acts 23:20

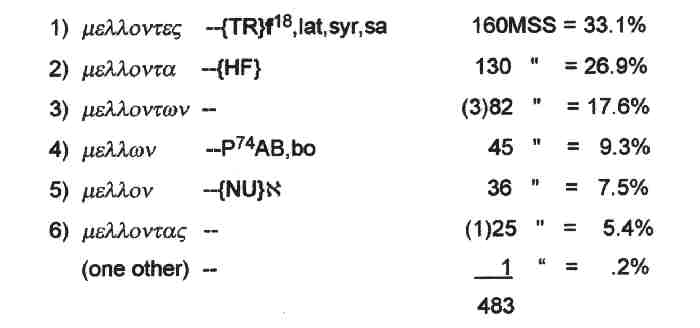

The Institut für neutestamentliche Textforschung in Münster, Germany has published an almost complete collation of the available MSS for selected variant sets in Acts. This permits a different statement of evidence than one usually sees—this and the following examples from Acts are based on that source.[24] The evidence looks like this:

Rather a dismaying picture—what to do? To begin, the variants are all participial forms of the same verb. The key seems to be the perceived referent or antecedent of the participle. Is it "the Jews", "the Sanhedrin" or "the commander"? The best answer from the point of view of the grammar is evidently "the Jews", which would require a masculine, nominative, plural form—the only candidate is variant 1). However, there were those who took the referent to be "the Sanhedrin"—the Alexandrian MSS have sunedrion next to the participle, separated only by wV. The grammar requires a neuter, accusative, singular form—variant 5). But, the Sanhedrin was made up of men, so perhaps some decided it would be more appropriate to make it plural—variant 2); and maybe even masculine besides—variant 6). Variant 3), being genitive, is really strange, unless somehow someone thought that the commander intended to inquire of the Sanhedrin, viewed as plural. Variant 4) presumably takes "the commander" as the referent, but puts the form in the nominative, sort of ad sensum since se is accusative. But variant 2) could also be referring to the commander, precisely masculine, accusative, singular.

What are the requirements of the context? "The commander" as referent does not fit. Not only was it not his idea, he sent Paul away that very night to forestall the possibility. (That the Jews should attempt to tell the commander what was in his mind is scarcely credible.) "The Sanhedrin" as referent really doesn't fit either. to sunedrion appears in the text as the object of a preposition, not as an initiating agent. It is "the Jews" that is the Subject of the main verb, and therefore of the two infinitives, and our participle is working with the second infinitive, "as ones intending to inquire."

Conclusion: variant 1) is the only one that really fits the context; it is also the best attested. Although it only musters 33.1% of the vote (including f18), it is also attested by the three ancient Versions—always weighty testimony.

2) Implications

Although the Majority Text is usually attested by over 95% of the MSS, every so often we get an unpleasant surprise where there is no majority reading at all. This case is as badly split as any I have seen. And yet, our "notes of truth" permit us to reach a convincing conclusion. "Number" fails us, but "Antiquity", "Variety" and "Continuity" do not. Although variants 4) and 5) are both ancient, so is 1), and it wins in "Variety" and "Continuity"; it also wins in "Reasonableness". So, I am cheerfully satisfied that mellonteV is the original reading.

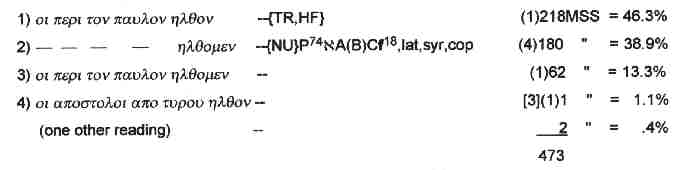

3) Example—Acts 21:8

The evidence looks like this:

Variant 3) would appear to be a not very felicitous conflation. Variant 2) best fits the context—since the beginning of the chapter, and before, the main participants have been presented in the first person plural. The closest finite verb on each side of the variant in question is emeinamen, 1st plural. The information in variant 1) is unnecessary but not objectionable; if variant 1) were original there would be no need to change it. Of course, if variant 2) were original there would be no need to change it either, unless some felt it was time to remind the reader who "we" was referring to. More likely it was the influence of the Lectionaries, since they have precisely variant 1). Since the MSS are quite evenly divided, the agreement of all three of the ancient versions makes variant 2) the better attested. (Again f18 agrees with an ancient tradition.)

3) Implications

Once again we do not have a majority reading, though the split is not quite so bad as in the prior case. "Antiquity" and "Variety" are clearly with variant 2), and so "Continuity" is presumably more with 2) than with 1), also. I conclude that variant 2) has the best claim to be printed in the text.

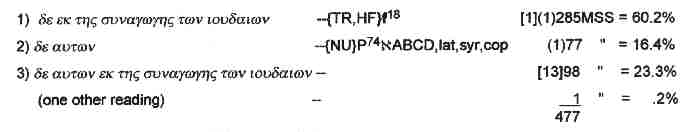

4) Example—Acts 13:42

The evidence looks like this:

I believe this variant set must be considered along with the presence of ta eqnh after parekaloun, but Aland's group did not include the second set. However, from UBS3 it appears that virtually the same roster of witnesses, including the three ancient versions (!), read variant 2) and omit "the Gentiles". Where then is the Subject of the main verb parekaloun? Presumably for those witnesses it would be the Jews and proselytes who had just heard Paul and wanted to hear it all over again the next Sabbath. So why are they (Jews and proselytes) mentioned overtly again in verse 43? And on what basis would the whole city show up the next week (v. 44)? But to go back to verse 42, why would the first hearers want to hear the same thing (ta rhmata tauta) again anyway? The really interested ones stuck with Paul and Barnabas to learn more (v. 43), just as we would expect.

The witnesses to variants 1) and 3) join in support of "the Gentiles", giving us a strong majority (over 80%). So the Subject of parekaloun is ta eqnh—they want a chance to hear the Gospel too, and the whole city turns out. It fits the context perfectly. So, variant 3) appears to be a conflation and the basic reading is variant 1). [If variant 3) is viewed as the original, variant 2) could be the result of homoioteleuton, but not variant 1).] The witnesses to variant 3), because they have "the Gentiles", are really on the side of variant 1), not 2), so presumably 1) may be viewed as having 80% attestation. For the witnesses to variant 1) the antecedent or referent of exiontwn must be Paul's group, since the Gentiles would presumably address their request to the teacher.

In variant 2) autwn presumably serves as Subject of both the participle and the main verb, but in that event the main verb should take precedence and the pronoun should be nominative, not genitive. However one might explain the motivation for such a change—from 1) to 2) and deleting "the Gentiles"—variant 2) is evidently wrong, even though attested by the three ancient versions (which troubles me). Perhaps someone faced with variant 1) took "of the Jews" to be the referent of the participle instead of modifying "synagogue" (like NKJV), and thought it should be Subject of the main verb as well—then, of course, "the Gentiles" were in the way and were deleted. Then 1) might have been shortened to 2) for "clarity".

4) Implications

This time we do have a majority reading, although not as strong as we could wish. "Antiquity" and "Variety" are with variant 2), although f18 confers "Antiquity" on variant 1) as well and therefore 1) wins in "Continuity". But, "Context" (the performance of the MSS in the near context) comes into play this time—it clearly favors variant 1), as does "Reasonableness"—it enables us to say that the attestation for 3) really goes with 1), not 2), so 1) comes out with over 80%. In short, variant 1) has "Number", "Continuity", "Context", "Reasonableness" and "Antiquity"; variant 2) has "Antiquity" and "Variety". I take it that the original text had: exiontwn de ek thV sunagwghV twn ioudaiwn parekaloun ta eqnh, etc.

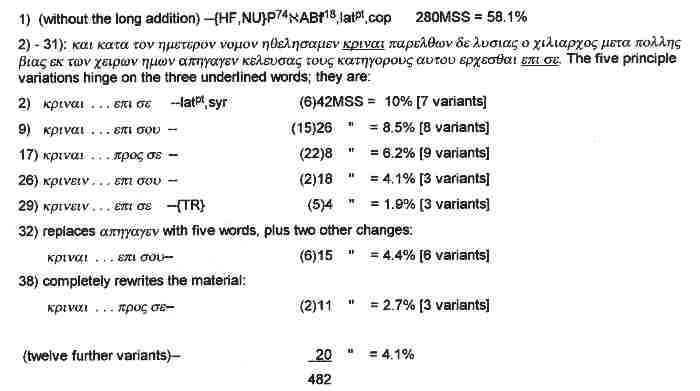

5) Example—Acts 24:6b-8a

The evidence looks like this:

Variant 2) presumably has the best claim to be the standard form of the addition: krinai beats krinein, epi beats proV, se beats sou. It is also attested by syr and latpt. However, although some form of the addition commands 41.9% of the MSS, there are no less than 51 variants!

What about the context? The addition makes good sense, and it fits nicely. But, it is not really necessary; that information Felix already knew. The text reads quite well without the addition also. I conclude that the short form was judged to be abrupt or incomplete, giving rise to the addition; presumably the Autograph did not contain it. Since Tertullian was an orator he may well have actually said what is in the addition, plus a good deal more besides, but did Luke write it?

5) Implications

The external evidence, though divided, is adequate to resolve this case: 58.1% against a severely fragmented 41.9%. The ancient versions, being divided, do not help us much this time. Although 58% is not a strong majority, by any means, still, the severe fragmentation of the 42% sort of leaves variant 1) without a worthy opponent. Variant 1) wins in "Antiquity", "Number", "Variety" and "Continuity", so I have no doubt that it is original. [The reading of the TR, variant 29), really has little to commend it.]

6) Example—Acts 15:34

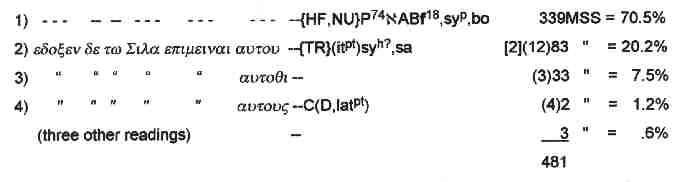

The evidence looks like this:

UBS and H-F agree that variant 1) is correct, and indeed verse 33 seems to require that Silas returned to Jerusalem; "they were sent back . . . to the apostles", and "they" refers to Judas and Silas. The "problem" is that in verse 40 Paul chooses Silas to accompany him, so he had to be in Antioch, not Jerusalem. Accordingly the longer reading was created to solve the "problem". The "some days" of verse 36 could well have been a month or two. From Antioch to Jerusalem would be a trip of some 400 miles. Silas had time to go to Jerusalem and get back to Antioch.

6) Implications

"Reasonableness" makes itself felt here; variant 2) introduces a contradiction, which the TR unfortunately perpetuates. Variant 1) also wins in "Number" and "Continuity". "Antiquity" and "Variety" are divided. Thus, with a majority of 70.5% variant 1) is the best candidate for the original reading.

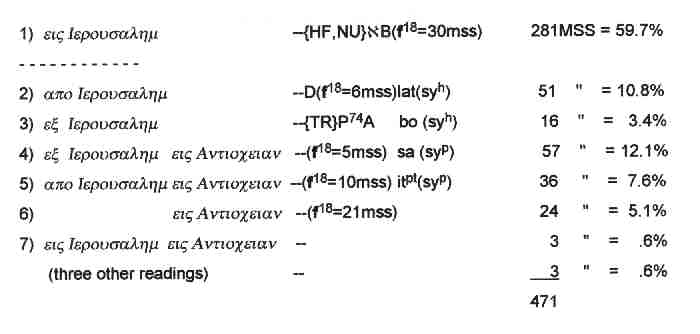

7) Example—Acts 12:25

This is the last example from Acts, and one that I consider to be especially difficult (it has the potential to be damaging). The evidence looks like this (I arbitrarily neglect margins and correctors, except for the early uncials):

There is indeed a majority reading, albeit a weak one, but within the context it can scarcely be correct.[25] Consider:

a) Acts 11:30, o kai epoihsan aposteilanteV, "which they also did, having sent . . . by B. & S." An aorist participle is prior in time to its main verb, in this case also aorist—their purpose is stated to have been realized. The author clearly implies that the offering did arrive, or had arrived, in Judea/Jerusalem.[26] Note that the next verse (12:1) places us in Jerusalem.

b) Acts 12:25 (12:1-24 is unrelated, except that vv. 1-19 take place in Jerusalem), BarnabaV kai SauloV —the action includes both.

c) Acts 12:25, upestreyan . . . plhrwsanteV thn diakonian, "they returned . . . having fulfilled the mission". Again, both the participle and the main verb are aorist, and both plural. "Having fulfilled the mission" defines the main verb. Since the mission was to Judea, which of necessity includes Jerusalem as its capital city, the "returning" must be to the place where the mission originated.

d) Acts 12:25, sumparalabonteV kai Iwannhn, "having taken John also along with them". Again, both the participle and main verb are aorist. Cf. Acts 13:13 where John returns eiV Ierosoluma.

Barnabas could be viewed as returning to Jerusalem, having completed his mission to Antioch, but this could not be said of Saul. There is no basis for supposing that Mark was in Antioch (cf. Acts 12:12) so he could return to Jerusalem with Barnabas and Saul. I conclude that "to Jerusalem" can hardly be correct here even though attested by 60% of the MSS. We observe that the other 40% of the MSS, plus the three ancient versions, are agreed that the motion was away from Jerusalem, not toward it. However, they are divided into five main variants, plus four isolated ones, so how shall we choose the original wording? I suppose that in a case like this we must indeed appeal to the basic "canon" of textual criticism, prefer the variant that best accounts for the origin of the others.

We must begin with presuppositions. Those who presuppose that the original text was not inspired, was not inerrant, will presumably choose variant 1).[27] It is the "harder" reading, being at odds with the context. Many copyists noticed the problem and attempted remedial action, producing variants 2), 3) and 6). Variants 4) and 5) would appear to be conflations and thus subsequent developments. Variant 7) is an obvious conflation. It is none the less curious that although "to Jerusalem" is evidently ancient, none of the early versions follows it.

I am among those who presuppose that the original text was indeed inspired and therefore inerrant; it follows that I am predisposed against variant 1), it evidently being in error.[28] What then? If 4) and 5) are conflations, then 2), 3) and 6) are earlier. Variants 2) and 3) would appear to be independent attempts to "fix" variant 1).[29] Forced to choose between 1) and 6), my presuppositions guide me to variant 6); but how did 6) give rise to 1)?

Well, a superficial reader could have focused on Barnabas and assumed that he was returning to Jerusalem, having finished his ministry in Antioch. Since 12:25 is the first mention of Barnabas (and Saul) after 11:30, and since 11:30 does not overtly say that they "went", "returned" or whatever, a superficial reader could easily decide that he had to get Barnabas back to Jerusalem. If the original of 12:25 read "to Antioch" this would be perceived as a problem, since to the superficial reader they would still be there, having never left. This "correction" evidently happened quite early, and possibly more than once, independently—if a number of separate copyists misunderstood the text in the way suggested, and felt constrained to "fix" it, presumably most of them would simply change "Antioch" to "Jerusalem".

Although 25.4% of the MSS, plus syp and sa, read eiV Antioceian, only 5.1% do so without conflation. But then, variant 3) has only 3.4% alone and 15.5% with the conflation. Variant 2) has 10.8% alone and 18.4% with the conflation. So, variant 6) beats 3) both alone and with conflations; variant 6) loses to 2) alone, but with conflations comes in ahead. I submit that variant 6) best explains the origin of all the others, and given the complexities of this case has the best claim upon our confidence. I conclude that the Autograph of Acts 12:25 read eiV Antioceian, which is presumably precisely what happened (they returned to Antioch); it also leads nicely into 13:1—comparing Acts 1:1 with Luke 1:3 we may reasonably conclude that Acts also is designed to be an orderly account.

It seems to me that there is only one way to "save" the majority variant here: place a comma between upestreyan and eiV, thereby making "to Jerusalem" modify "the ministry". But such a construction is unnatural to the point of being unacceptable—had that been the author's purpose we should expect thn eiV Ierousalhm diakonian or thn diakonian eiV Ierousalhm. The other sixteen times that Luke uses upostrefw eiV we find the normal, expected meaning, "return to". As a linguist (PhD) I would say that the norms of language require us to use the same meaning in Acts 12:25. Which to my mind leaves eiV Antioceian as the only viable candidate for the Original reading in this place.

7) Implications

The whole contour of the evidence is troubling. It is evident that all the variants were created deliberately; the copyists were reacting to the meaning of the whole phrase within the context (in this situation it will not do to consider the name of each city in isolation; the accompanying preposition must also be taken into account). Variants 2) through 6) are all votes against 1), but we must choose one of them to stand against 1)—the clear choice is 6). "To Jerusalem" has "Number", "Antiquity" and "Continuity". "To Antioch" has "Antiquity," "Variety," "Continuity" and "Reasonableness". As Burgon would say, this is one of those places where "Reasonableness" just cannot be ignored, but it is not alone; "to Antioch" also wins in "Variety" while "to Jerusalem" wins only in "Number" (not strong; "Antiquity" and "Continuity" are shared). So, the "notes of truth" confirm our conclusion that eiV Antioceian is the original reading in this place.

It will have been observed that I included f18 in the statements of evidence (in Acts). f18 in Acts corresponds to Mc in Revelation as used in the H-F Majority Text (Mc = Hoskier's "Complutensian" family, about 33 mss). I am convinced that Mc represents the best line of transmission (but not necessarily perfect) in Revelation and thus am especially interested in the performance of f18 in Acts (and Paul's epistles). In Acts f18 represents a core of 70-75 MSS which are usually in agreement. Not so in Acts 12:25—they split five ways. Variant 1) has the most, 30 mss, followed by 6), 21 mss. All those with "Antioch" = 36 mss; all those without it also = 36 mss [but six of them are against variant 1)]. Evidently f18 is not monolithic; I would like to see it receive detailed study.

8) Example—Luke 6:1

Shall we read sabbatw deuteroprwtw (variant 1) or sabbatw (variant 2)? Variant 1) is attested by A,C,D,K,Q,P,Y, some 1,800 other Greek MSS, lat,syh,goth,arm,geo, and a number of early Fathers. Variant 2) is attested by P4,À,B,L,W, some dozen other Greek MSS, itpt,syp,pal,cop,eth,Diat. The attestation for variant 2) is certainly early and varied, but it scarcely has more than 1% of the vote! The parallel passages in Matt. 12:1 and Mark 2:23 both have "the sabbaths" (plural). Although deuteroprwtw doubtless made excellent sense in the first century, we have since lost the relevant cultural information. So variant 1) is definitely the "harder" reading and the offending word could easily have been deleted, here and there, especially in places like Egypt and Ethiopia where the niceties of Jewish culture would probably not be known. That both Matthew and Mark use the plural suggests that Luke was simply more specific. Here we have an eloquent illustration of the faithfulness that characterized the vast majority of copyists down through the centuries of copying by hand. Even though they did not understand the word deuteroprwtw, presumably, they none the less reproduced it verbatim in their copies. We owe them a debt of gratitude.

8) Implications

Variant 2) has "Antiquity" and "Variety". Variant 1) also has "Antiquity" and "Variety", plus "Continuity" and "Number" (overwhelming). "Reasonableness" may not be urged against variant 1), in this case, because the difficulty arises from our ignorance, not from the context or demonstrable facts of history, science or whatever. The "note" of "Respectability" enters in this case: the specific MSS listed for variant 2) are all of demonstrably inferior quality. I have not the slightest doubt that variant 1) is the original reading.

I will now discuss the implications of overwhelming number. At the beginning of this section reference was made to a "ceiling" of attestation, and I suggested 80%. Where a reading commands 80% (not to mention 90% or 95%) attestation it evidently dominated the stream of transmission, or genealogical tree, and the chances of an error doing so are minute. (Of course an error could have done so, here and there, but each time we "cash that check" it increases the odds against any subsequent use of that expedient—a dozen bad checks are enough to close the account.) I personally would not grant even the theoretical possibility that an error could command so much as 95% of the attestation, and probably not even 90%. (My hypothetical "bad checks" would therefore fall between 80% and 90%. Please note the term hypothetical; I have yet to encounter an actual example.) Thus, "Jeremiah" in Matt. 27:9 must be original since it is attested by over 98% of the Greek MSS. In 1 John 5:7-8 fully 99% of the Greek MSS do not have the "three heavenly witnesses". Mark 16:9-20 is attested by no less than 99.8% of the extant MSS!

But why put the ceiling at 80% rather than 70%, or even 60%? Well, the choice is arbitrary. Anything with over 2/3 attestation is most likely to be correct, but there is a significant difference between 70% and 80%—a 70/30 split gives a 2.33:1 ratio, but an 80/20 split gives a 4:1 ratio, almost twice as strong (90% gives a 9:1 ratio while 95% gives a 19:1 ratio and 98% gives a 49:1 ratio!). The accidents of history could easily result in an uneven transmission such that an unworthy reading might come out with 60% attestation, or even more. I have seen several readings with up to 75% support that I suspect will prove to be in error. Where the attestation is badly split (or splintered) we must indeed "weigh" the witnesses, not just count them. On the basis of complete collations we must establish MS families or groupings and determine the "batting average" or credibility quotient of each one—special attention should be given to the groups that score the highest.

9) Example—Revelation 4:8

The statement of evidence is based on Hoskier and the H-F Majority Text.[30] The question is whether "holy" occurs three times (variant 1) or nine times (variant 2). Variant 1) is attested by A,P,Md,e,g,h, most "independents" and 38% of Ma, for a total of 108 MSS. Variant 2) is attested by (À),Mc,b,f,a for a total of 95 MSS. Ma and Mb usually work together and derive from a common exemplar, I believe. Md and Me usually work together and derive from a common exemplar. Md,e and Ma,b are usually at odds, while Mc lines up now with one, now with the other, about half and half. This means that we have three independent lines of transmission, and they are older than Aleph since Aleph conflates them (in other places). The group led by Ma is sometimes called "Q" and includes Mf and Mg. Mh and the "independents" are hard to evaluate.

That Ma,b,f are in agreement presumably indicates that the exemplar Ma,b read variant 2). In that event the "Q" MSS that read variant 1) have deviated from their exemplar, either by mixture or independent simplification (if we took those 23 MSS away from variant 1) the numerical attestation would shift significantly). Surely it is more likely that variant 2) should be changed to variant 1) than vice versa. In fact, try reading "holy" nine times in a row out loud—it starts to get uncomfortable! Since in the context the living ones are repeating themselves endlessly, the nine "holies" are both appropriate and effective. I take it that Mc and Ma,b preserve the original, while Md,e went astray.

9) Implications

Because of the three (at least) independent lines of transmission, and because of the shifting alignments among them and their sub-groups, Revelation is the only book where we encounter many variant sets with no majority reading—about 150, plus another 250 where the majority is less than 60%. Those who argue that Majority Text theory makes its best case in Revelation are precisely mistaken; the reverse is the case. Hoskier's collations permit us to group the MSS empirically, so in evaluating variants we need to deal with the groups, not just count individual MSS. Burgon's "notes" are often difficult to apply in cases such as the 400 mentioned; most of the notes divide, giving no clear verdict. On the basis of its performance throughout the book, I would say that Mc has the best "batting average", but if there are basically three independent lines of transmission then two against one should carry the day. Here we have Mc and Ma,b against Md,e, in favor of variant 2)—if the three "holies" were the original reading, however could the nine "holies" come to capture two of the independent streams?

Conclusion

So then, how are we to identify the original wording? First we must gather the available evidence—this will include Greek MSS (including Lectionaries), Fathers and Versions. Then we must evaluate the evidence to ascertain which form of the text enjoys the earliest, the fullest, the widest, the most respectable, the most varied attestation.[31] It must be emphasized that the strength of the "notes of truth" lies in their cooperation. They must all be considered and taken together because the very fact of competing variants means that some of the notes, at least, cannot be satisfied in full measure. But by applying all of them we will be able to form an intelligent judgment as to the independence and credibility of the several witnesses.

Actually, the work of Hoskier and Wisse[32] shows us that it is possible to group the MSS empirically, on the basis of a shared mosaic of readings. Once this is done we are dealing with independent groups, not individual MSS. Thus, Wisse's study in Luke reduces 1,386 MSS to 37 groups (plus 89 "mavericks").[33] These must be evaluated for independence and credibility. The independent, credible witnesses must then be polled. I submit that due process requires us to receive as original that form of the text which is supported by a clear majority of those witnesses; to reject their testimony in favor of our own imagination as to what the reading ought to be is manifestly untenable.

I am sure that if Burgon were alive today he would agree that the discoveries and research of the last hundred years make possible, even necessary, some refinements on his theory. I proceed to outline what I consider to be the correct approach to N.T. textual criticism. (I venture to call it Original Text Theory.)[34]

1) First, OTT is concerned to identify the precise original wording of the N.T. writings.

2) Second, the criteria must be biblical, objective and reasonable.

3) Third, a 90% attestation will be considered unassailable, and 80% virtually so.

4) Fourth, Burgon's "notes of truth" will come into play, especially where the attestation falls below 80%.

5) Fifth, where collations exist, making possible an empiric grouping of the MSS on the basis of shared mosaics of readings, this must be done. Such groups must be evaluated on the basis of their performance and be assigned a credibility quotient. A putative history of the transmission of the Text needs to be developed on the basis of the interrelationships of such groups. Demonstrated groupings and relationships supersede the counting of MSS.[35]

6) Sixth, it presupposes that the Creator exists and that He has spoken to our race. It accepts the implied divine purpose to preserve His revelation for the use of subsequent generations, including ours. It understands that both God and Satan have an ongoing active interest in the fate of the N.T. Text—to approach N.T. textual criticism without taking due account of that interest is to act irresponsibly.

7) Seventh, it insists that presuppositions and motives must always be addressed and evaluated.

[1]Burgon, The Traditional Text, p. 29. I acknowledge with alacrity my considerable indebtedness to Dean Burgon, especially for arousing me to look at the evidence, but my treatment of the various "notes" is not identical to his. Fee says of these "notes", "all of which are simply seven different ways of saying that the majority is always right" ("A Critique," p. 423). It should be apparent to the reader, just at a glance, that Fee's statement is irresponsible. It is a clear illustration of the carelessness and superficiality which characterize much of his critique.

[2]Sturz, pp. 67-70.

[3]Burgon, The Traditional Text, pp. 107, 255-56. Regarding this statement of evidence Fee says the following: "I took the trouble to check over three-quarters of Burgon's seventeen supporting Fathers and not one of them [emphasis Fee's] can be shown to be citing Matthew!" (Ibid., pp. 418-19). (The term oxoV, "vinegar," also occurs in the near-parallel passages—Mark 15:36, Luke 23:36 and John 19:29.)

Before checking the Fathers individually, we may register surprise at Fee's vehemence in view of his own affirmation that it is "incontrovertible" that "the Gospel of Matthew was the most cited and used of the Synoptic Gospels" and that "these data simply cannot be ignored in making textual decisions" (Ibid., p. 412). We are grateful to Fee for this information but cannot help but notice that he himself seems to be "ignoring" it. We might reasonably assume that at least nine of Burgon's 17 citations are from Matthew. But we are not reduced to such a weak proceeding.

Even though a Father may not say, "I am here quoting Matthew," by paying close attention to the context we may be virtually as certain as if he had. Thus, although all four Gospels use the word "vinegar," only Matthew uses the word "gall", cole, in association with the vinegar (and Acts 8:23 is the only other place in the N.T. that "gall" appears). It follows that any Patristic reference to vinegar and gall together can only be a citation based on Matthew (or Ps. 69:21). When Barnabas says, potizein colen meta oxoV (7:5), can there be any doubt as to his source? When the Gospel of Peter says Potisate auton colen meta oxouV (5:16), must the source not be Matthew? When Gregory of Nyssa says, cole te kai oxei diabrocoV (Orat. x:989:6), can there be any question at all? It may be noted in passing that Alford's Greek N.T., in loc., says plainly that Origen and Tertullian both support the "Byzantine" reading under discussion. (The research reflected in the discussion above was done by Maurice A. Robinson and kindly placed at my disposal.)

Note also that Irenaeus wrote, "He should have vinegar and gall given Him to drink" (Against Heresies, XXXIII:12), in a series of O.T. prophecies that he says Christ fulfilled. Presumably he had Ps. 69:21 in mind—"they gave me gall for food, and in my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink"—but he seems to have assimilated to Mt. 27:34 (the "Byzantine" reading). The Gospel of Nicodemus has, "and gave him also to drink gall with vinegar" (Part II, 4). The Revelation of Esdras has, "Vinegar and gall did they give me to drink." The Apostolic Constitutions has, "they gave him vinegar to drink, mingled with gall" (V:3:14). Tertullian has, "and gall is mixed with vinegar" (Appendix, reply to Marcion, V:232). In a list of Christ's sufferings where the readers are exhorted to follow His example, Gregory Nazianzus has, "Taste gall for the taste's sake; drink vinegar" (Oratio XXXVIII:18).

Whatever interpretation the reader may wish to give to Fee's statement, noted at the outset, it is clear that the reading "vinegar" in Matthew 27:34 has second century attestation (or perhaps even first century in the case of Barnabas!). The reading in question passes the "antiquity" test with flying colors.

[4]Anyone who offers a conjectural emendation in the face of such attestation is claiming that his authority is greater than that of all the witnesses combined—but since such a person is not a witness at all, does not and cannot know what was written (having rejected 100% attestation), his authority is nil.

[5]Westcott and Hort, p. 45.

[6]Lake, Blake and New, pp. 348-49.

[7]Burgon, The Traditional Text, pp. 46-47.

[8]Cf. Epp, "The Claremont Profile Method for Grouping New Testament Minuscule Manuscripts," Studies in the History and Text of the New Testament in Honor of Kenneth Willis Clark, Ph.D. (Studies and Documents, 29) ed. B.L. Daniels and M.J. Suggs (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1967), pp. 27-38.

[9]Burgon, The Traditional Text, pp. 50-51. Anyone who has been taught that Burgon followed "mere number" will perceive that there is more to the story than that.

[10]Cf. Streeter, p. 148; Tasker, "Introduction to the Manuscripts of the New Testament," Harvard Theological Review, XLI (1948), 76; Metzger, The Text, p. 171; Clark, "The Manuscripts of the Greek New Testament," p. 3.

[11]Burgon, The Traditional Text, p. 52.

[12]Ibid., p. 59.

[13]It seems to me to be frankly impossible that an original reading should have absolutely disappeared from the knowledge of the Church for over a millennium and then pop up magically in the twelfth century. I here refer to a single witness—hundreds of medieval MSS of necessity reflect an ancient text.

[14]F. Wisse, The Profile Method for Classifying and Evaluating Manuscript Evidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982).

[15]Westcott and Hort, p. 275; Zuntz, The Text, p. 84.

[16]Burgon, The Traditional Text, p. 58.

[17]"How ill white hairs become a fool and jester!" (Shakespeare's King Henry IV, part 2, Act V, Scene V, about line 50).

[18]Burgon, The Traditional Text, p. 62.

[19]Burgon, The Revision Revised, pp. 77-78.

[20]Burgon, The Traditional Text, p. 65.

[21]Colwell, "Scribal Habits."

[22]Burgon, Ibid., pp. 66-67.

[23]The New Testament in Greek: The Gospel According to St. Luke, Vol. I, ed. The International Greek New Testament Project (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), p. 74.

[24]Text und Textwert der Griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments, ed. Kurt Aland (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1993).

[25]Note that scholars with presuppositions so diverse as an Alford, a Burgon, a Hort or a Metzger have reached the same conclusion.

[26]In Acts the author seems almost to use "Jerusalem" and "Judea" interchangeably, perhaps to avoid repetition. E.g. 11:1 Judea, 11:2 Jerusalem (were the Apostles not in Jerusalem, or immediate environs?); 11:27 Jerusalem, 11:29 Judea, 11:30 the elders (would not the ruling elders be in Jerusalem?); 12:1-19 took place in Jerusalem, but v. 19 says Herod went down from Judea to Caesaria; 15:1 Judea, 15:2 Jerusalem; 28:21 letters from "Judea" probably means Jerusalem.

[27]Please note that I an not saying that they are the only ones who might make such a choice, nor even that they will necessarily do so.

[28]Please note again that I am speaking only of myself. I am making the point that presuppositions must always be taken into account since they heavily influence the interpretation of the data. This is true of all practitioners in any discipline.

[29]upostrefw ek is unprecedented (in the N.T.), upostrefw apo occurs four times, upostrefw eiV occurs 17 times. The reading of the TR is highly improbable, statistically speaking. If we had to choose between apo and ek, apo would win on all counts.

[30]Hoskier, Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse; Hodges and Farstad, The Greek New Testament according to the Majority Text.

[31]Cf. Burgon, The Revision Revised, p. 339.

[32]The collations published in the Text und Textwert series edited by K. Aland represent an important contribution with reference to the variant sets treated.

[33]Please note that I am here concerned with the principle involved. Of course different scholars may argue for different alignments, assign individual MSS to different groups, etc., but none of this alters the principle that the MSS can be grouped, empirically.

[34]I have thought of resurrecting the term "traditional", but since Burgon and Miller are not here to protest, I hesitate; besides, that term is no longer descriptive. Terms like "antiochian" or "byzantine" carry an extraneous burden of antipathy, or have been preempted. So here's to Original Text Theory. Since I really do believe that God has preserved the original wording to our day, and that we can know what it is on the basis of a defensible procedure, I do not fear the charge of arrogance, or presumption, or whatever because I use the term "original". All textual criticism worthy the name is in search of original wording.

[35]Please note that I am not referring to any attempt at reconstructing a genealogy of MSS—I agree with those scholars who have declared such an enterprise to be virtually impossible (there are altogether too many missing links). I am indeed referring to the reconstruction of a genealogy of readings, and thus of the history of the transmission of the Text.